Madison’s new Planned Development district provides a rigorous yet flexible pathway for innovative land-use that encourages sustainable development and green-building. Through the PD rezoning process OM Village was able to codify the designations portable shelter and portable shelter community, allowing OM Village to house Madison’s homeless; a project that would not have been possible without the PD district.

- Category

- Land Use and Development

- Subcategory

- Planned Development Zone

- Adopted By

- City of Madison, WI

- Applies To

- Projects that do not fit within any other zone

- Owned By

- City of Madison

- Managed By

- Department of Planning, Community & Economic Development

- Participation

- Community input in zoning code rewrite process

- Year of Adoption

- 2011

- Current Version

- 2012

- Update Cycle

- Recent Action

- Amendments adopted 10/16/2012

- Code/Policy

- Planned Development District

- Pursuant to

- Section 28.097 Madison Zoning Code (see pg. 85)

- Referenced

- Wisconsin Statutes, Section 66.1001, Comprehensive …

n 2007 the City of Madison, WI, decided to update their 40+ year old zoning code to better reflect the development preferences of modern Madisonians, and to comply with Wisconsin’s Smart-Growth law. Through an inclusive public process, community members worked with the Zoning Department to outline a user-friendly zoning code, representative of community values and desired land-uses, that complemented the smart growth principles and strategies outlined in their 2006 Comprehensive Plan.

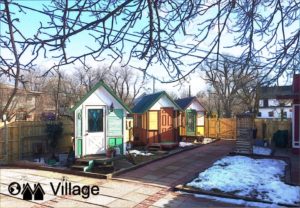

The purpose of the PD District is to provide a regulatory pathway for innovative, integrated, and/or sustainable development projects that are not permissible in any other zone. While the compliance path is rigorous, it has allowed for such projects as OM Village, Madison’s first tiny home village for the homeless. Through the PD option, OM Village was able to amend their zoning code to allow for nine ‘portable shelters’ arranged in a mixed-use ‘portable shelter community’.

| Policy Title | Purpose of Policy |

|---|---|

| 28.097 Planned Development District(see page 85) | To provide a rigorous yet flexible regulatory framework for innovative, integrated, and/or sustainable development projects that would otherwise not be permissible in any other zone. |

| Wisconsin Statutes, Section 66.1001, Comprehensive Planning/Smart Growth Law’ | Applicable law requiring every municipality in WI to engage in public comprehensive planning of their community, and to create and/or update a Comprehensive Plan with matching Zoning Code/Map by 2010. |

PUDs and variations of PDs are not a new zoning method and certainly not unique to Madison, WI. With roots dating back to post WWII development planning (late 1940s), PUDs have maintained an enabling function, allowing for a mixture of land uses otherwise untenable to the standard zoning of the larger area. As one Madison source makes note, “PUD regulations typically [and traditionally] merge zoning and subdivision controls so that large areas can be master planned with design flexibility in meeting zoning requirements for uses, density, dimensional standards and other development regulations, in order to achieve more creative design and greater public benefits…and are typically planned and zoned on a case-by-case basis, resulting in a set of specific negotiated standards for each project” (pg 4).

In the case of Madison, PUDs became the default pathway for development projects that didn’t conform to the single-use (conventional or Euclidean) zoning typical of Madison’s 1960s era zoning code. The zoning code rewrite intended to make PUDs a less necessary approach. Zoning Director Matt Tucker makes note, “the [PUD] process has been used too much in recent years, so the city has tried to craft zoning districts that reflect the types of developments being approved as PUDs, while ‘raising the bar’ for when it’s necessary to seek PUDs…Let’s save the PUD for the truly exceptional project.” It is this ‘raising of the bar’ that is especially notable and indicative of an innovation perhaps unique to Madison.

To address the multitude of issues present in the outdated zoning code, the city staff made two decisive moves:

- “the Common Council initiated a Zoning Code Rewrite Advisory Committee (ZCRAC), including representatives from a variety of public and private stakeholder groups, to oversee and facilitate the zoning code rewrite process, and act as a decision making body and a liaison to the constituencies of each member in the committee;” and,

- “the City retained the services of a team of architectural consultants whose responsibility involved the actual preparation of the new Zoning Code and Zoning Map”

The zoning code rewrite process involved eight steps and took place over roughly two years (For a detailed description of each, see Zoning Code Analysis pg 2-3). A large component of the process involved public participation, which included the following elements:

- A series of community meetings held at four points over course of process;

- Focus groups and informal meetings with representatives of neighborhoods, the development community, and other interested parties;

- Mailings and email bulletins to stakeholder groups and individuals;

A section on the City’s web site dedicated to the project, with announcements, meeting summaries, background information, and links to other resources”.

Among the many changes that took place during this three-year zoning code rewrite process was the recalibration of what qualifies for a Planned Development District (PD). By creating mixed-use hybrid zones and redefining the PD policy’s purpose and requirements, the zoning staff made the development process more efficient and conducive to contemporary development practices while simultaneously giving truly innovative land-use projects a chance to become manifest.

The stated purpose of the PD District is “to provide a regulatory framework that facilitates the development of land in an integrated and innovative fashion, to allow for flexibility in site design, and to encourage development that is sensitive to environmental, cultural, and economic considerations, while also promoting the use of “green building technologies, low-impact development techniques for stormwater management, and other innovative measures that encourage sustainable development”. It is important to note, however, that the PD District specifically applies to projects with desired uses incongruent within all other zones. Section 28.097(1) clarifies:

“Because substantial flexibility is permitted in the base zoning districts, the PD option should rarely be used. It is intended that applicants use the PD option only for unique situations and where none of the base zoning districts address the type of development or site planning proposed…”

Section 28.097(1) gives the following examples of what might qualify for a PD zone: “redevelopments, large-scale master planned developments, projects that create exceptional employment or economic development opportunities, or developments that include a variety of residential, commercial, and employment uses in a functionally integrated mixed use setting.” The evident application to “larger scale projects” seems appropriate given that most smaller scale projects would likely fit within one of the flexible hybrid zones already in place, disqualifying them from the PD rezoning process.

The PD District is assessed and approved on a case by case basis and therefore the scope is limited to the project’s site only. Section 28.097(1) continues:

“Approval of a Planned Development District requires a zoning map amendment, and shall result in the creation of a new site-specific zoning district, with specific requirements and standards that are unique to that planned development.”

As an example, OM Village, Madison’s first tiny-home village for the homeless, utilized the prescriptive PD zone to author the zoning text specific to their project, allowing for land-use illegal elsewhere in the city. Discussions with City officials prompted the Occupy Madison organization to pursue the PD rezoning process in order to accommodate their project’s more innovative aspects (tiny homes, shared cooking/cleaning facilities, light manufacturing studio, commercial space, office space, community garden, etc.). After a lengthy public process where City officials, concerned residents of a nearby neighborhood, and the Occupy Madison organization worked to articulate a general development plan and specific implementation plan, the designations for Portable Shelter and Portable Shelter Community were codified as were a full list of uses (conditional and otherwise) permitted for their site.

- “Portable Shelter” is identified as: “any movable living quarters, more than 150 square feet in area, used as an individual’s permanent place of habitation. For purposes of this definition, a permanent place of habitation is established when an individual lives in a portable shelter for four consecutive months.”

- “Portable Shelter Community” is described as: “any site, lot, parcel, or tract of land designed maintained, intended or used for the purpose of supplying a location or accommodations for more than three portable shelters and shall include all buildings included or intended for use as part of the Portable Shelter Community. A ‘portable shelter community’ shall not include a ‘portable shelter mission’.”

While the site-specific nature of this innovative zoning text makes replicability no less challenging, the simple fact that such an innovation has a prescriptive pathway through the PD rezoning process is an empowering facet of Madison’s new zoning code.

The compliance path begins with a pre-design conference and a concept presentation, both of which involve discussing design direction, context, and potential impacts of the project with the city’s Planning Division, Zoning staff, and Urban Design Commission. Following these informational meetings and with the feedback given from the city, the design/development team must articulate and submit a general development plan and a specific implementation plan. Generally speaking the ‘general development plan’ (GDP) is an overview of the project’s design. It includes (but is not limited to): the proposed zoning text, key features of the project, and an analysis of the potential economic impact to the surrounding community. The ‘specific implementation plan’ (SIP) also includes aspects of the project’s design (topography, grading, existing/proposed landscaping and structural features, utility access, etc.) but additionally requires proof of financing capability, a detailed construction schedule, and any by-laws/agreements that govern the organizational structure of the development or any of its associated common services, public open areas, shared facilities, etc. To get approved both the GDP and SIP must be reviewed by the Urban Design Commission, the Planning Commission, and the Common Council, and be found in compliance with the design objectives and standards outlined in 28.097 (1-4).

Subsection (2) outlines the ‘standards for approval’ which include:

- “[Demonstrating] that no other base zoning district can be used to achieve a substantially similar pattern of development.”

- Shall be in compliance with the development/redevelopment goals of the Comprehensive Plan.

- “Shall not adversely affect the economic health of the City or the area of the city where the development is proposed.”

- Demonstrating that each phase of implementation can be completed.

- Shall coordinate/conform to architectural design context of surrounding area (a hallmark of ‘form-based zoning codes’)…

The compliance path for a PD zone is rigorous to say the least, some might even say burdensome, but this can be viewed as in the City’s and developer’s best interests. The standards and requirements force developers to work out the kinks in their project’s designs early, challenging them to think-through, articulate, and argue for certain aspect of their design. This practice, albeit cumbersome, arguably makes for more successful implementation and management of the project.

| Madison’s Comprehensive Plan, applicable section, “Adaptability and Sustainability” (PDF see pg 73-75). | Wisconsin ‘Smart Growth’ law: history, purpose, etc. |

| OM Village case study, an example of the type of project that qualified and was approved for a PD district. | Madison’s 2008 Zoning Code Analysis |

Based on the input from a diversity of residents and stakeholders, various objectives were outlined to address hurdles present in the old code. Most relevant to this study are Project Objectives 4, 5, and 10, which express a desire for the new Zoning Code to include: “hybrid zoning codes (incorporating land use-based and form-based provisions were appropriate),” “mixed-use zoning districts,” and promotion of sustainable development practices (pgs 1-2). Each of these objectives has influenced the current purpose and use of the PD district, mostly by opening up development possibilities through other zones and thus limiting the necessity and application of the PD zone to “truly exceptional projects.”

Some of the alterations to the PUD district addressed in the new PD code include:

- “Creating a minimum area for PUDs

- Setting requirements for open space protection; a specified percentage (20%) should be protected open space

- Defining street layout; internal and external connection standards

- Provisions of transit, pedestrian and bicycle facilities where appropriate

- Requirements to meet sustainability benchmarks such as green building design, or low-impact stormwater management”

In reference to this last requirement, the zoning code rewrite more broadly hoped to encourage certain sustainability initiatives through policy. Some of the policies discussed during the rewrite process include:

- “Reducing Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) by removing barriers to or providing incentives for compact mixed‐use development.

- Encouraging the development of solar, small wind and other renewable energy systems in all or selected residential districts;

- Encouraging accessory units and live‐work units in selected residential districts;

- Allowing small‐scale recycling facilities in residential districts;

- Encouraging local food production by encouraging community gardens, Community Supported Agriculture, and similar food production initiatives;

- Encourage or require low‐energy‐input landscaping;

- Require protection of the urban forest;

- Offer density/height bonuses for green roofs; make green roofs eligible as open space;

- Limit impervious coverage; encourage pervious pavements” (pgs 12-13).

This points to a clear objective of those rewriting the code to allow for policies that encourage ‘sustainable development’ initiatives. It also reaffirms a statement made by Tucker that “[the city] is trying to write a green code.”

Prior to the zoning code rewrite, developers with high hopes of building mixed-use projects (combining commercial and residential for instance) often had to go through the lengthy and costly PUD rezoning process in order get an exemption from the single-use restrictions built into the old zoning code. As one article makes note, “the [intensive PUD] process may have contributed to the sense that Madison was against development, even ‘anti-business’” (statement made by Brian Ohm). The inefficiency in this process in terms of both time and money no doubt acted as a disincentive for many developers and likely prevented many interesting and socially beneficial infrastructural projects from becoming manifest. The ‘simple’ recalibration of Madison’s zoning code as a whole (creating relevant, flexible, ‘mixed-use’ hybrid-zones and limiting PUDs by raising the bar for what qualifies for the PD rezoning process) seems to have had a positive economic impact for all parties since the new zoning code took effect in 2011.

It is important to note that the purpose of the PD district is not to make ‘innovative’ projects financially cheaper, but to ensure that these innovative projects have all their ducks in a row before the implementation stage. It’s easy to see how some developers might perceive the PD rezoning process as too high an investment in time and money, and in this respect it arguably still disincentivizes certain innovative projects. For other more social-wellness oriented groups like Occupy Madison, who utilized the prescriptive PD pathway to create a tiny home village for Madison’s homeless, the effort and costs were a small price to pay in order to achieve safety and shelter for unhoused members of the Madison community.

The potential for other jurisdictions to apply a similar policy and/or to integrate aspects of Madison’s PD zone into their own policies is high. Most municipalities already have some form of a PD zone that can be amended (or used outright) in order to achieve innovative development practices, however, if one finds that their municipality doesn’t have a PD zone nor any analogous pathway towards innovative land-use, implementing some of the methods employed by Madison might expand the legal capability of your jurisdiction to allow for more innovative development.

Madison’s approach involved rewriting/remapping most of their zoning code but other less extensive options are possible. Depending on one’s situational context, and assuming the underlying goal (of providing easier options for sustainable development) is held, one could focus on amending an existing zone or creating a new category altogether using Madison’s PD zone as a guide. Apart from sections specific to the city of Madison’s zoning/planning judicial structure (e.g. ‘Common Council’, ‘Urban Plan Commission’, etc. approving project plans), Madison’s code language for their PD district seems in essence universal (in that it simply sets up the regulatory structure through which projects can apply), but jurisdictions can/should decide for themselves which aspects to keep, leave out, or add too so as to make the policy more contextually appropriate to one’s ‘place.’

The major funding was for the Zoning Code Rewrite Advisory Committee which was included in the Planning Division’s Operating Budget.

Zoning Administrator

- https://www.buildinginnovations.org/wp-content/uploads/96fe1d36-51e0-43da-9fb4-59ffcfe73cc2.pdf

- https://www.buildinginnovations.org/wp-content/uploads/summary_of_wisconsin_comp_plan.pdf

- https://www.buildinginnovations.org/wp-content/uploads/OM-Conditional-Approval-Letter-1.pdf

- https://www.buildinginnovations.org/wp-content/uploads/v2c2.pdf